China’s export imperative is not a slogan. It is a macro constraint

Issue 231, January 19th January 2026

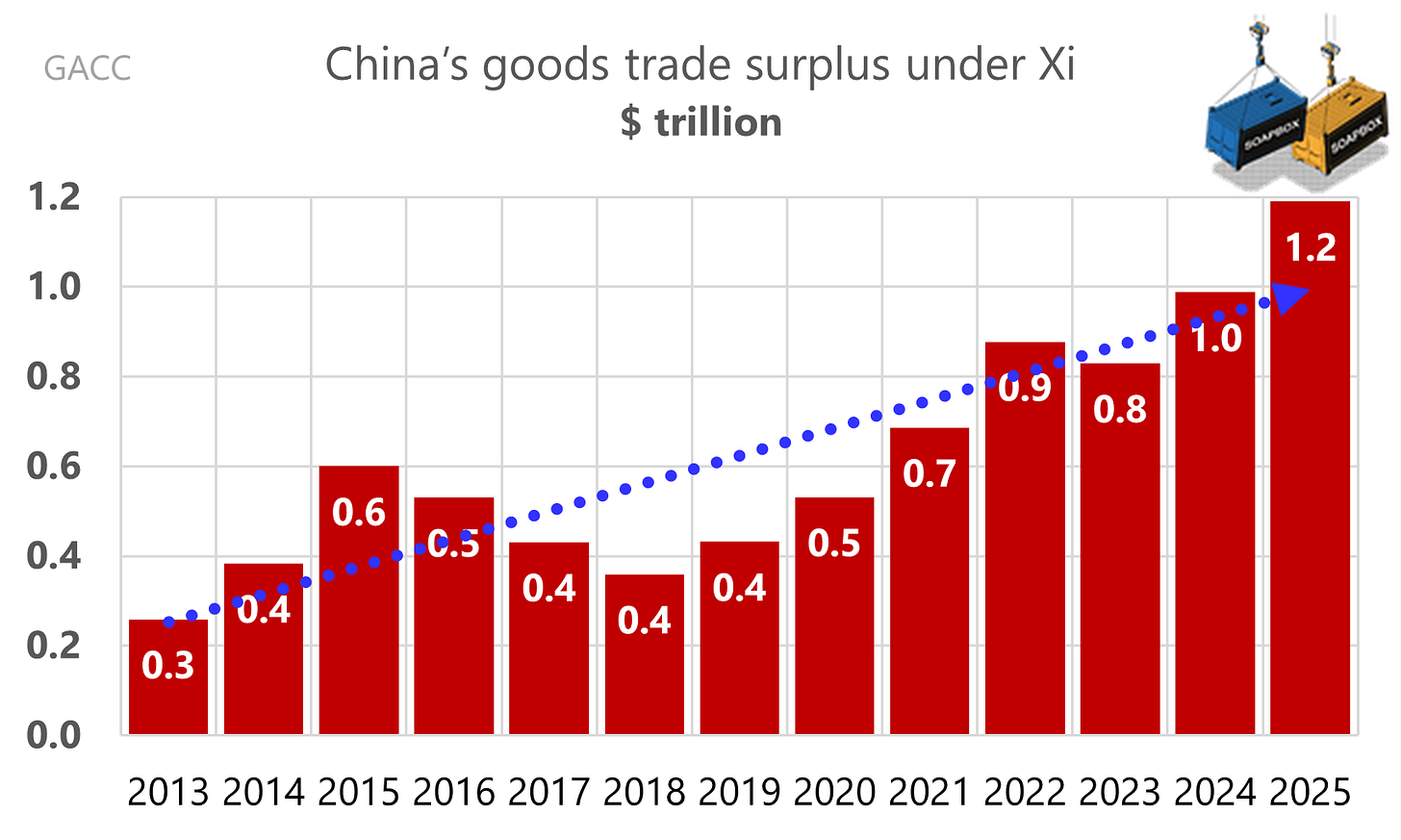

In 2025, China reported a record goods trade surplus of nearly $1.2 trillion. As a back-of-the-envelope comparison, that net export flow is roughly equal to about 1% of the rest of the world’s GDP.

China’s goods trade surplus in the Xi years 2013–2025

Xi Jinping took power in late 2012. When domestic demand is soft and the property engine no longer pulls the economy forward, planners lean on the one part of the system that can still deliver scale quickly: manufacturing. That means keeping factories busy, jobs steady, and cash flow moving across supply chains

This export imperative can sit inside many narratives at once. Beijing can speak about “opening up” and “win-win”. It can also present surging shipments to the Global South as “helping development” through affordable goods and infrastructure inputs.

What trading partners see is the same

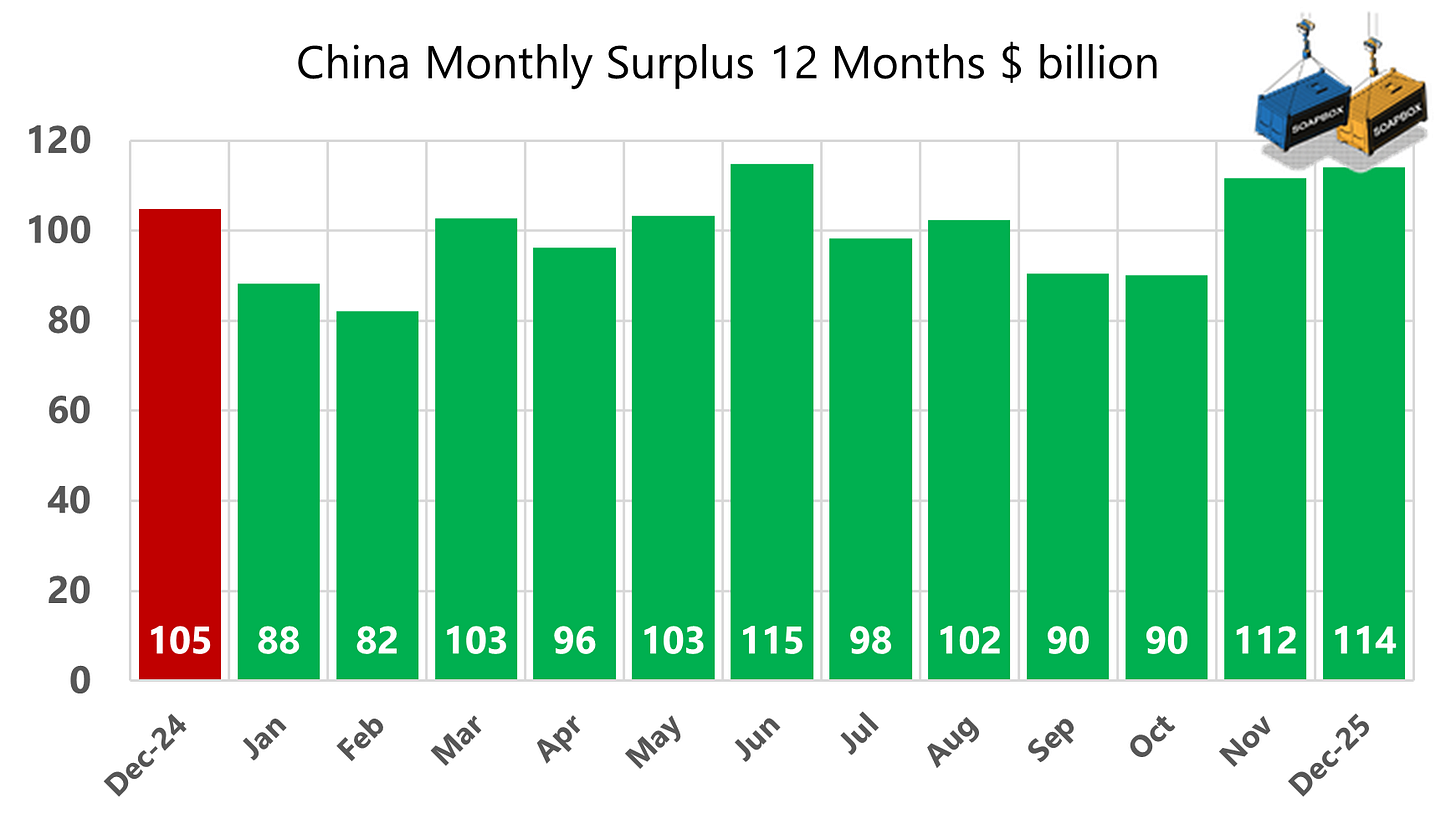

Partners see widening bilateral surpluses and deeper dependence on Chinese supply. The story may be framed as solidarity, but the outcome often looks like mercantilism. Exports become the pressure valve, helped by close management of the yuan and tight controls on capital outflows that keep export prices competitive while keeping domestic savings at home. In 2025, the surplus averaged around $3.3bn a day.

China’s 2025 surplus averages $3.3bn a day

China’s goods surplus in the Xi years looks less like a smooth climb and more like a staircase. For much of the 2010s it sat in the $0.4 to 0.6 trillion range, with a mid-decade peak and then a long stretch of sideways movement. That plateau pointed to the limits of the old model and helps explain why Xi later pushed his “dual circulation” strategy, after consolidating power and removing term limits.

Then comes the pandemic era and, instead of fading, the surplus steps up. From 2020 onwards, the bars ratchet higher almost year after year, reaching about $1.2tn by 2025.

A fair reading is that this is not just “China exporting more”, but the outcome of two forces pulling in the same direction: strong external competitiveness and a domestic economy that has struggled to absorb as much output as before. When households and firms at home are cautious, the system does what it’s built to do: it looks outward. The trendline is a polite version of the story. The bars on the first graph are the punchline.

That is impressive in an accounting sense. For trading partners, it is also a warning that 2026 may bring another year of aggressive, price-competitive Chinese exports.

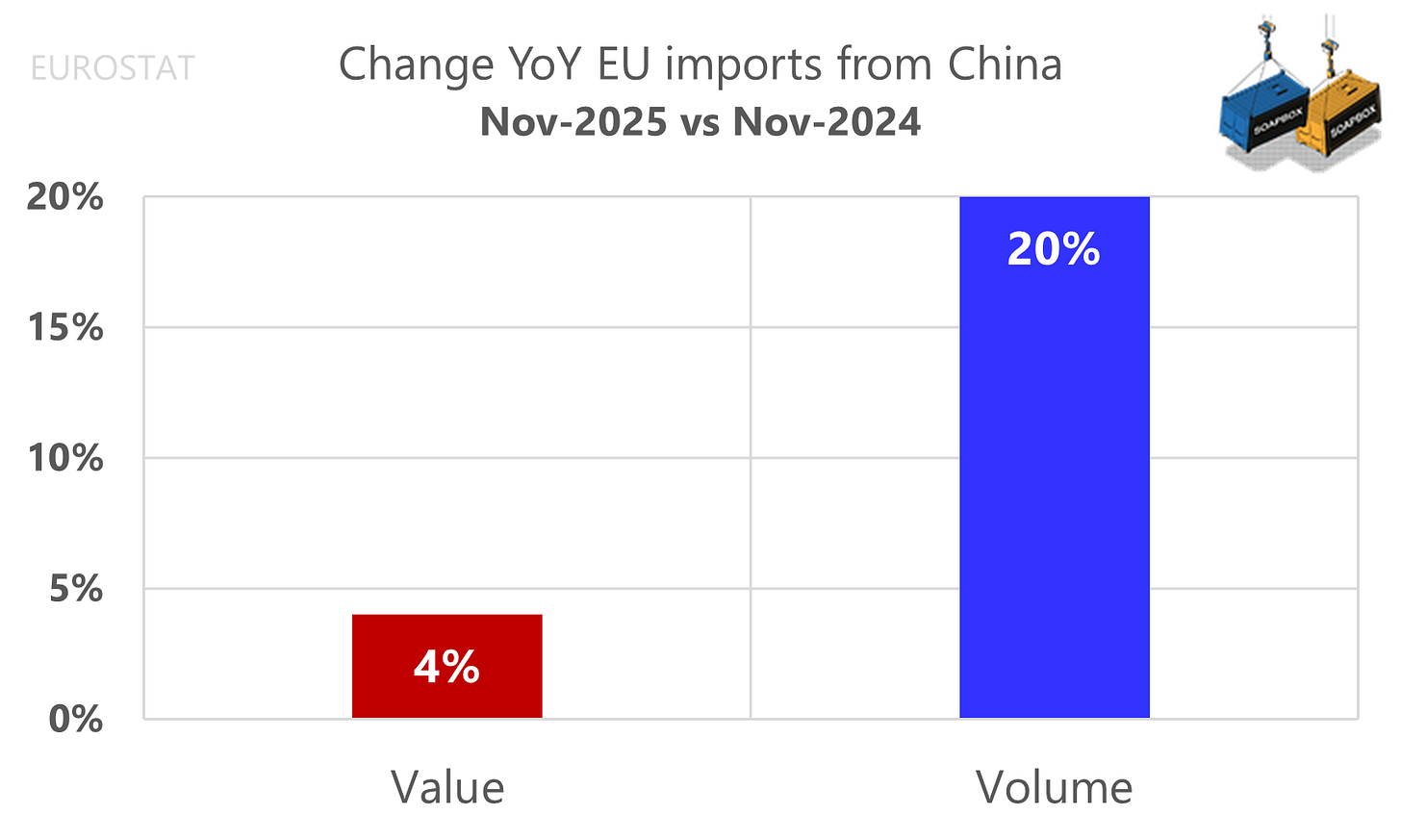

China’s overcapacity at work, more volume than value

In November 2025, EU imports from China were up 4% by value year on year, but volumes rose 20%.

The November chart shows how this works in practice. If EU imports from China rise 4% by value but 20% by volume, the implied unit values fall by roughly 13%. That is what an export imperative looks like on the ground. More goods move, priced to clear, and the competitive pressure lands directly on domestic producers. Value data can understate the shock. Volume shows the real footprint.

Market access in China is only part of the answer for the EU

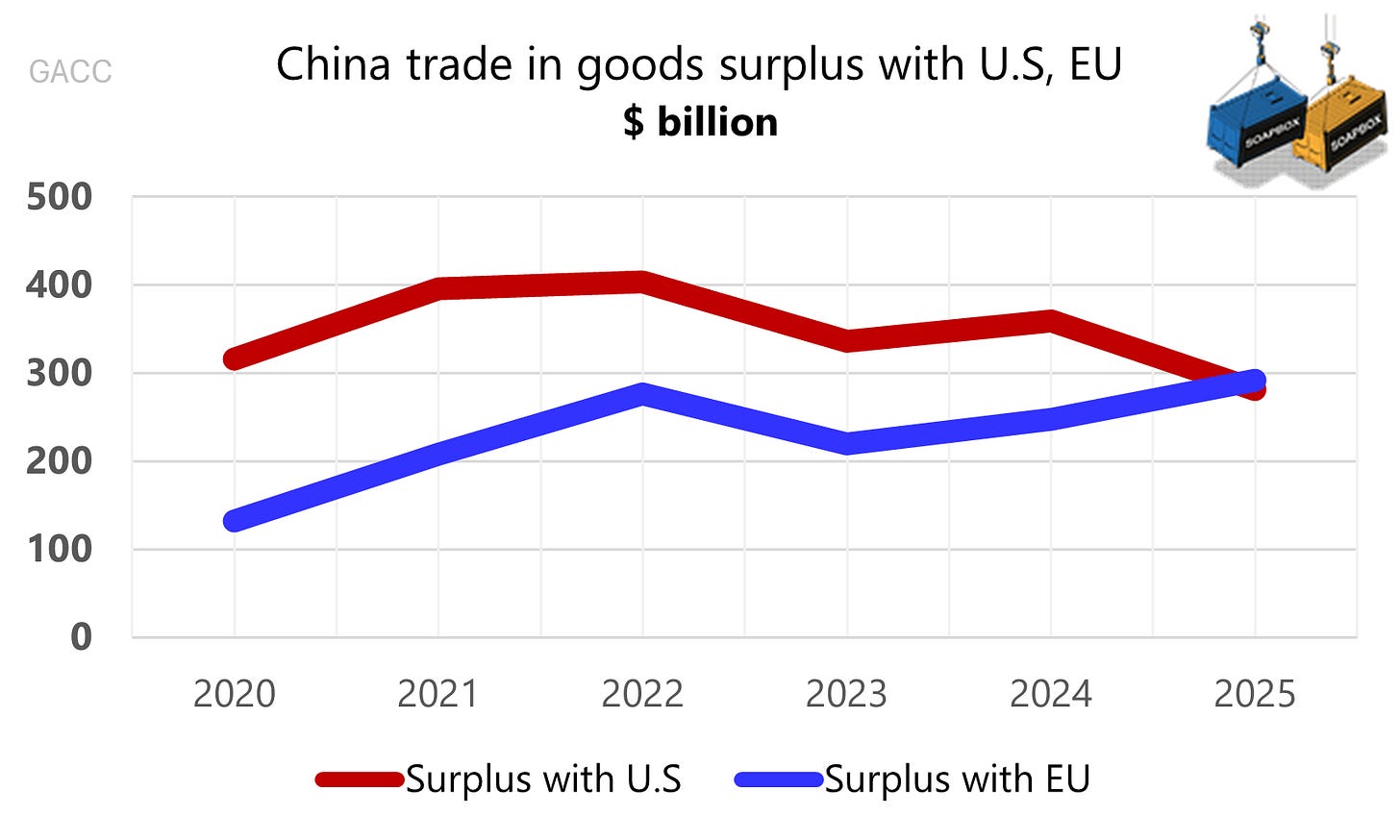

As long as China’s system needs external demand to absorb capacity, Europe should expect continued surplus pressure, more disputes framed around “overcapacity” and subsidised competition, and a policy response that shifts from rhetoric about rebalancing to practical measures that reduce exposure. The gap in EU–China trade below shows why.

In November 2025, the EU’s trade deficit with China averaged €1.07 billion a day

EU imports from China rose 4% year on year in November 2025, while exports fell 1%. As a result, the EU’s trade deficit with China widened to €32.2 billion, up from €30.3 billion a year earlier.

China’s surplus does not disappear, it relocates by imperative

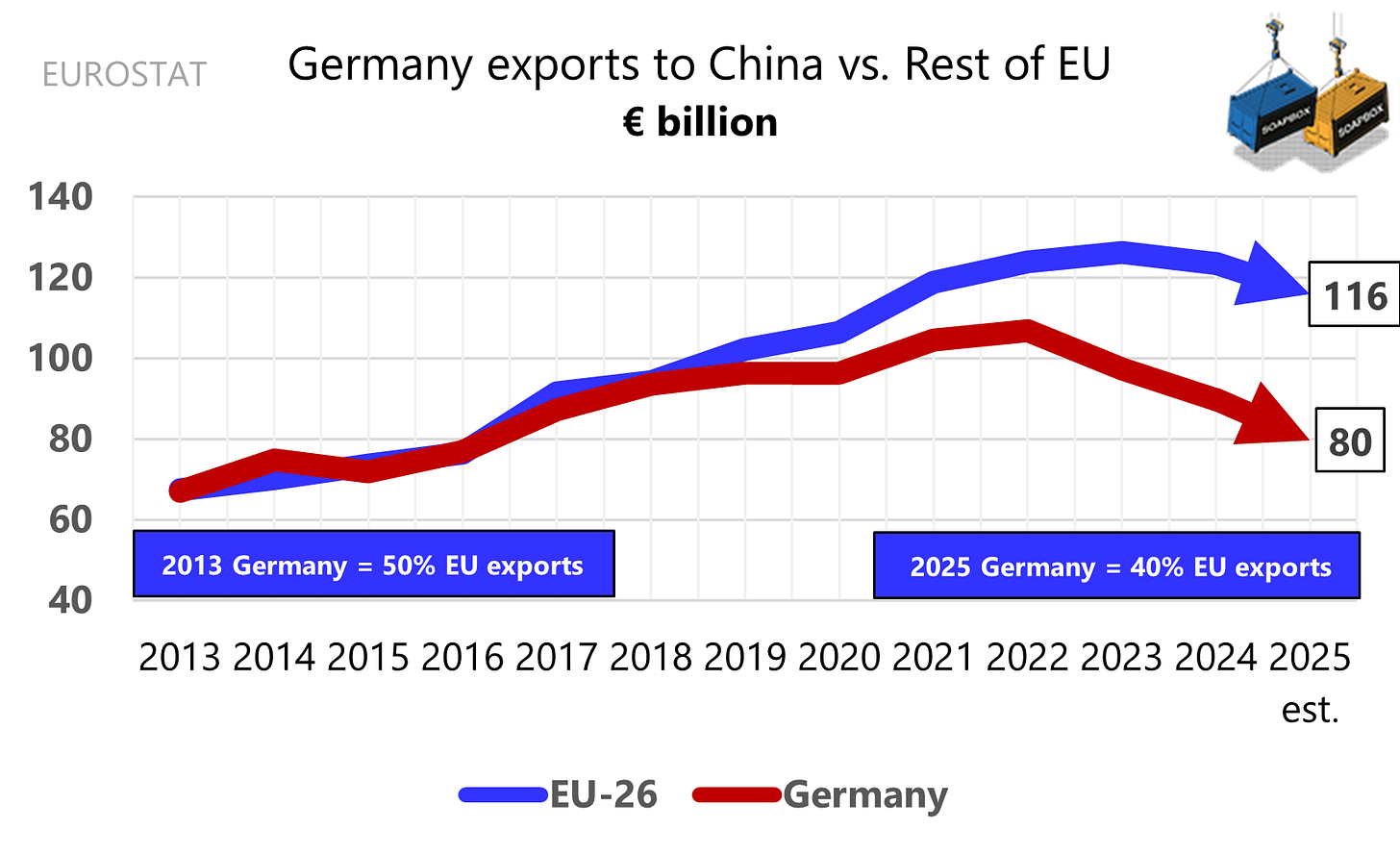

Germany is hit hardest by the slump in exports to China, but the rest of the EU is starting to feel it too

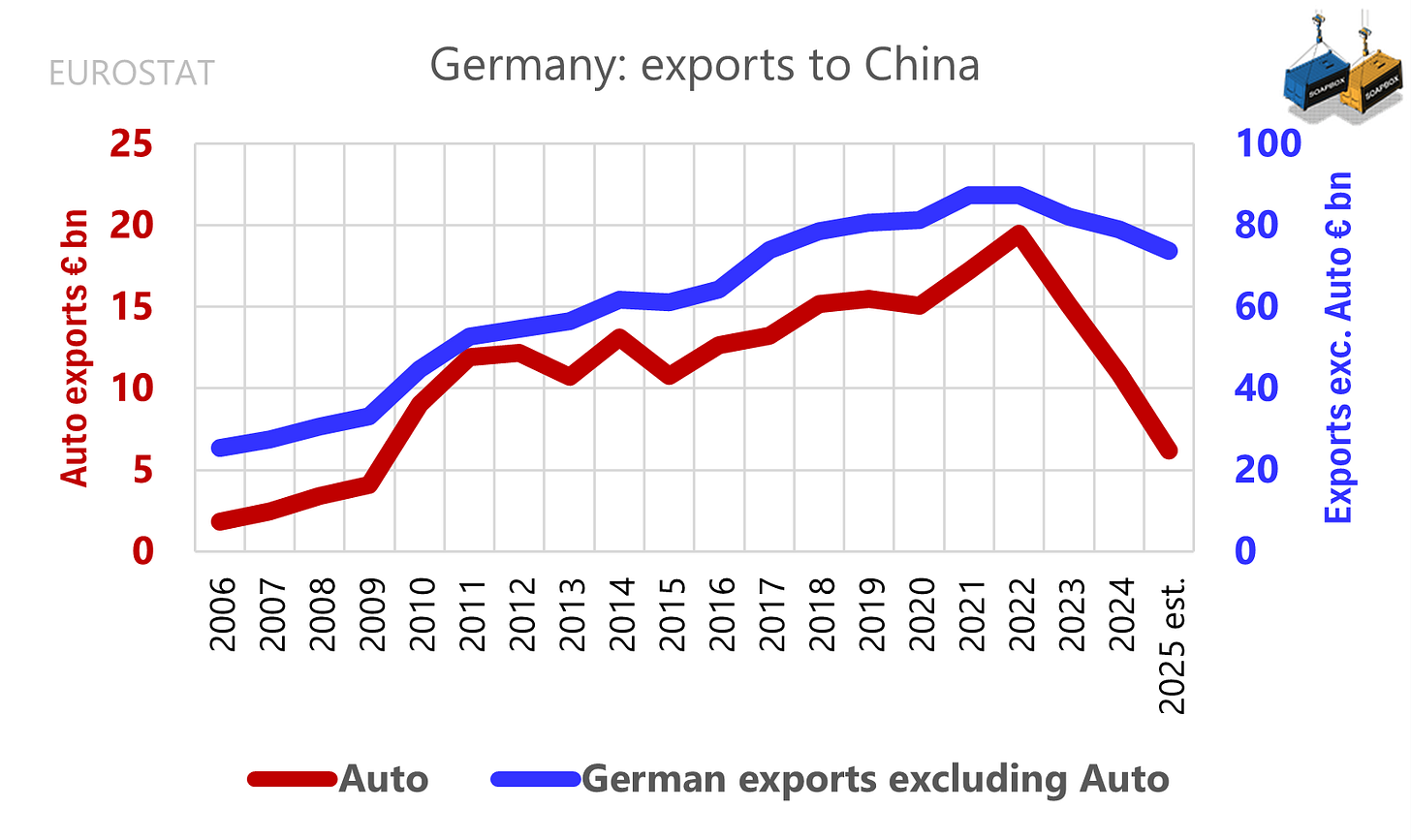

Germany’s China export problem comes on four wheels

The pain is concentrated. The change is what matters: the auto drop is larger and faster than the drift in the rest. Germany isn’t suddenly losing China across the board

It’s losing it where it used to overperform: cars.

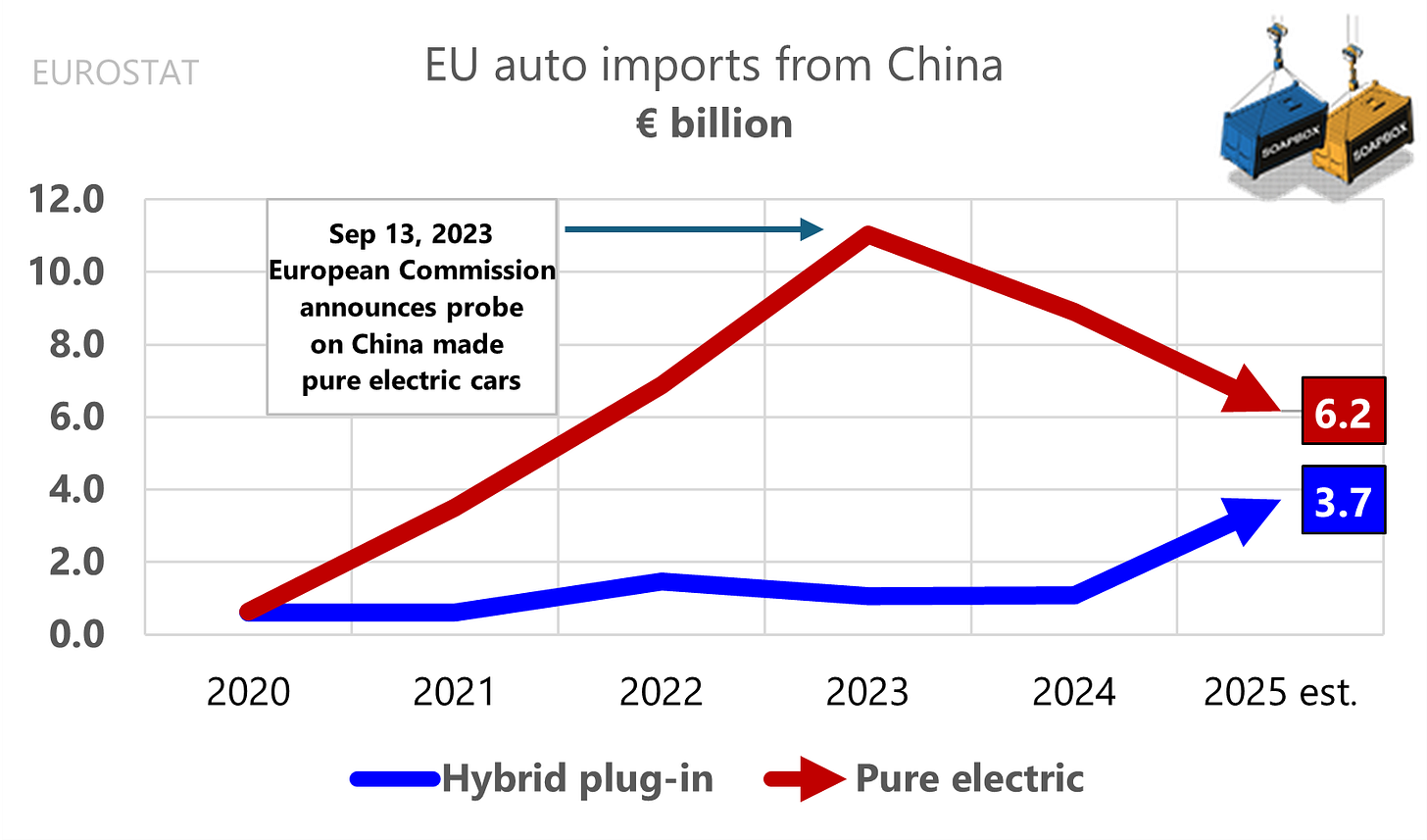

EU guidance on minimum prices for Chinese electric cars is a pathway not proof of a deal

China is presenting this as a deal on minimum prices to replace EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. The EU is presenting it as procedure, not a settlement. The Commission has published a guidance for Chinese exporters on how to propose price undertakings, including model-specific minimum import prices and possible volume or investment commitments. That is a pathway to replace duties for approved exporters, not proof that the two sides have already agreed the minimum prices.

Crucially, the EU says acceptance would require an Implementing Decision and an amendment of the regulation imposing the existing measures (with Member State voting). That’s a procedural pathway , not proof that the EU and China have already agreed a final minimum-price deal.

The European Commission’s investigation, the higher tariffs approved on electric cars, and Tesla’s decision to build a new factory near Berlin, together with consumer preferences, have all contributed to a drop in China’s electric-car exports to the EU. In 2025, we estimate these exports will be 44% below their 2023 peak by value. At the same time, plug-in hybrid imports from China are up 143% year on year in 2024.

EU response seems both policy and tariff based. On the policy side, the EU is considering measures that could allow sales of some combustion-engine cars beyond 2035. On the trade side, the surge in plug-in hybrids from China is inevitably drawing policymakers’ attention, and, as with electric cars, higher tariffs may end up on the table.

All in all, this adds pressure to China’s export imperative, encouraging Beijing to present a manufacturer-by-manufacturer compliance framework as a “tariff agreement” with the EU, even though it is essentially guidance for individual firms.

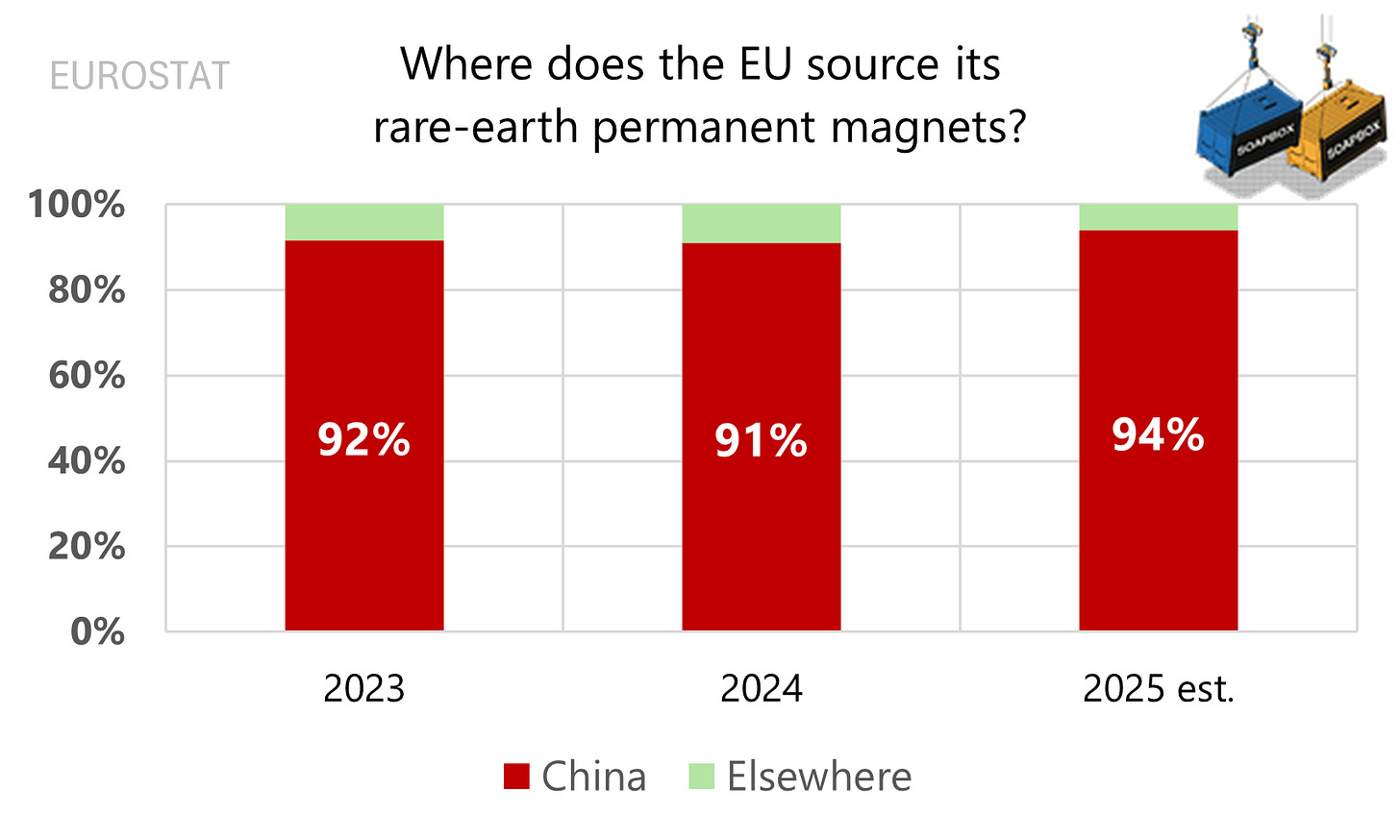

Once the EU started counting, China had 90% of the magnets

Before 2023, the EU did not have a dedicated HS code for rare-earth permanent magnets, so it could not separately track how much of these imports came from China. In 2025, the EU imported 19,900 tonnes, of which 18,700 tonnes came from China

EU and MERCOSUR sign free trade agreement

On January 17 the two blocs signed a free trade agreement in Paraguay. The pact still needs the approval from the European Parliament which has the final say. Panama’s president, whose country is an associate state of Mercosur without a vote, joked that the best way to overcome France’s opposition to the deal is to host a beef barbecue together, paired with French wine. Not a bad idea, is it?

We are committed to sharing with you the best trade analysis we have to offer. If you would like to share something with us, feel free to comment in the section below or drop us a line at soapbox.trade@gmail.com

Phenomenal breakdown on the surplus mechan ics. That $3.3bn-per-day fig puts it in perspective way better than the annualized number. When I saw the November EU data showing 20% volume growth versus 4% value, it became obvious this isnt normal trade expansion its deliberate price-dumping to keep capacity humming. Dual circulation was always gonna end up more circular than dual.